Rethinking health and social care post Covid-19

The social care sector in the UK is staring into an abyss of shrinking care capacity and exponentially rising demand, driven by factors such as chronic underfunding and a lack of joined-up thinking, not to mention the unprecedented challenges of the coronavirus pandemic. This has led to talk about the ‘new normal’, but what will […]

The social care sector in the UK is staring into an abyss of shrinking care capacity and exponentially rising demand, driven by factors such as chronic underfunding and a lack of joined-up thinking, not to mention the unprecedented challenges of the coronavirus pandemic.

This has led to talk about the ‘new normal’, but what will the new normal be for social care? How will this change the ways in which care is delivered and, crucially, what impact will this have on patients?

As the new normal emerges and social care responds to the extraordinary situation we’re faced with, never has there been a greater need for technology-led transformation challenges. In this report we investigate at the major challenges facing the UK care sector post Covid-19 and detail how technology can lead the rethink of the sector and enable fundamental change in care delivery.

Steve Morgan discusses why failing to change is failing those in need.

Failing to change is failing those in need

Covid-19 has turned the daily rhythms and routines of the world as we knew it upside down, reaching deep into our lives. The profound, lasting impact of the pandemic will be felt for many years and decades to come.

While it’s hard to think of any sector or group of individuals that hasn’t been affected by Covid-19, as the pandemic has spread, carers and those receiving care have been significantly impacted.

The NHS has been radically mobilised to respond to the acute needs of people infected with the virus, at the same time as delivering scaled-back non-Covid-19 health care. Social care, weakened by years of declining real-times public funding and rising demand, has been reeling from this impact of the virus.

During the pandemic, along with colleagues from Agilisys, I spent time working with NHSX to identify solutions that could be deployed regionally or nationally to tackle the problems in health and social care created by the virus. This highlighted the significant issues that need to be addressed if we are to rescue the beleaguered sector, which is facing challenges on an unprecedented scale – and showcased why technology must be at the forefront of delivering better care for citizens.

In this report I discuss the major challenges the sector is facing and look at how technology can transform the way social care is delivered, drive a more holistic view of social care, and help to deliver the long overdue locality paradigm. We’re at the stage where failing to change is failing those in need. That also means we’re at the point where the opportunities for technology-led transformation are at their greatest.

I hope you find this report useful in sparking plenty of conversation and new ways of thinking.

Steve Morgan, Partnership Director, Agilisys

Agilisys and our work with NHSX

As part of the UK response to the Coronavirus pandemic, NHSX launched a programme to engage with innovative technology providers to identify solutions that could be deployed regionally or nationally to tackle the problems created by the virus.

Given our strong relationship with DHSC and NHS nationally, Agilisys and other private sector companies, were proud to provide to support this activity.

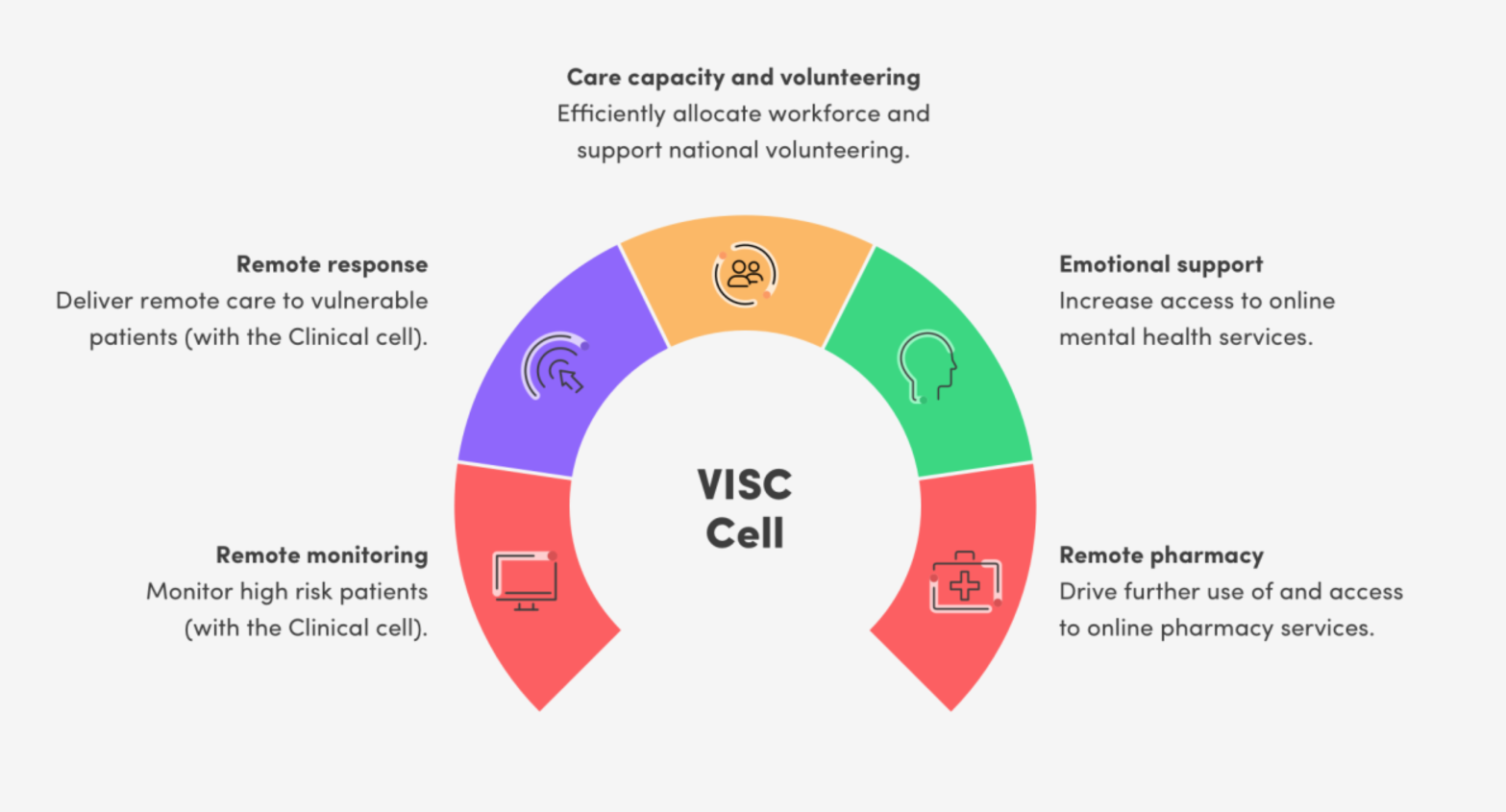

The areas within the programme, with which we were most closely aligned, were the Vulnerable, Isolated and Social Care (VISC), and NHS Staff and Social Care Workers (People) cells. These cells focused on the following solutions:

We worked with NHSX user research teams, and multiple private sector representatives (from Telco to Pharma) to develop a deep and broad insight into the social care challenges caused by the pandemic. We are fortunate, to now be able to take these learnings into our national engagement with local authorities to inform, support and transform services ready for the new normal.

The major challenges facing UK care post Covid-19

The challenges and pressures facing social care are well publicised – and nothing new. However, those problems have been exacerbated by Covid-19.

Detailed research of publicly available information from organisation such as The King’s Fund, Office for National Statistics (ONS), Age UK and many more, highlighted and reinforced (once we aggregate the information) the major issues facing the sector at the moment.

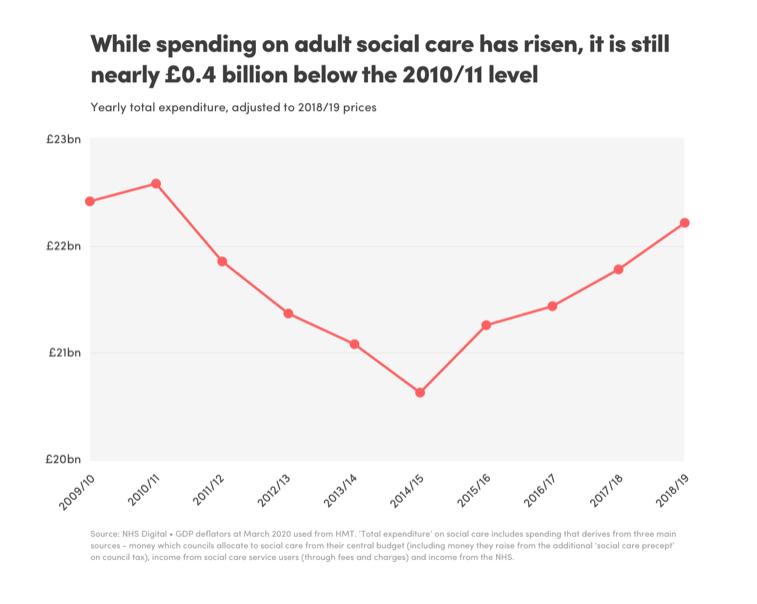

A key data point and very probably the major influencing issue is funding. Austerity is a point of debate, but it cannot be argued that austerity has directly impacted the delivery of care in the UK with the annual funding erosion mirroring the degradation in care quality and consistency. According to The Kings Fund, while funding has increased since 2014/15, it is still £400m behind the 2010/11 position, the initiation of austerity.

Funding isn’t the only problem facing the sector. Bringing together and examining the excellent publicly available information highlighted several additional key influencing factors:

Challenge 1: Age

According to Statista, the median age of the UK population between 2010 and 2020 has increased from 39.5 years to 40.5 years.

This stat does, however, mask the truth that the UK has a rapidly ageing population. The ONS estimates that, by 2030, one in five people will be aged 65. Within 50 years, over 65s will have increased by 8.6 million, a population roughly the size of London, while the 85+ age group is the fastest growing demographic, set to double to 3.2 million by 2041 and treble by 2066 to 5.1 million – equivalent to 7% of the population.

If we want a real demonstration of the changes in life expectancy, 23.4% of male and 29.2% of female babies born in 2018 will survive to the age of 100.

Is the increase in age good news? Let us look at the next influencing factor.

Steve Morgan discusses the challenge of an ageing population.

Challenge 2: Health and disability

Again, using official trending figures from the ONS, measuring the impact of health can be achieved using ‘healthy life expectancy’, which is based on the number of years expected to be spent without a disability, i.e. in good health. Even with the huge strides made within healthcare, UK life expectancy has risen more quickly than health expectancy.

Based on 2016 figures, the healthy life expectancy average in England at the age of 65 is 9.9 years. If we take the increase of the 85+ age group mentioned earlier, then the slower rate in growth of the healthy life expectancy points to a growing demand for intervention (health or care). If life expectancy continues to outstrip healthy life expectancy, this will give rise to a near exponential increase in demand over the coming decades.

With these statistics in mind, can the increasing demand be managed?

Challenge 3: The pandemic’s impact on the economics of care

The final factor to examine is the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the economics of care. Many thousands of deaths, fears of a second wave, the awful stories of a reckless approach to care homes are all we see in the daily news. However, there is a more covert impact within the care sector that it potentially disastrous. Understanding the potential impact means we need to look at some underlying economic factors.

There have been many discussions, even arguments regarding displacing care provision from the public to the private sector. In whatever way we view the situation, a study reported in The Guardian stated that 84% of all UK residential care home beds are provided by the private sector (or profit driven companies they stated emotively). For many of the private sector providers, the term profit is equally emotive, operating on low (less than 10%) margins, while facing cost pressures such as the change in the minimum wage that affects the 1.5m care workers who are traditionally low paid (though highly skilled).

In additions, care provision, most notably domiciliary care, the cost profile is greater than 90% labour-force and hence every 1% increase in wage results in a consequential reduction in profit, resulting in an unsustainable business. Saga, Care UK & Housing, Care 21, Mears and Mitie have all withdrawn from the publicly funded home care market with Mitie selling its home care business for £2 in 2017.

Steve Morgan explains how Covid-19 has impacted the economics of care.

Challenge 4: Pressure on local authorities

As a result of the Care Act changes in 2014, local authorities have a statutory obligation to ‘shape’ the care market and ensure adequate care provision of a sufficiently high quality to meet demand. If this obligation were being met by private sector providers, the delayed discharge measure (i.e. waiting for a domiciliary care plan) would not have increased from 12,777 in August 2010 to 33,520 in March 2018 (NHS England 2017).

A key impactor of this is evidenced by a survey of directors of adult social care in 2017 by the Association of Directors of Adult Social Care, which had already found that 39% had experienced home care providers ceasing to trade in the previous six months and 37% had experienced contracts being handed back.

Challenge 5: The “self-funders”

In 2016/17, self-funders spent £10.6bn on privately purchased care and self-funders typically pay 41% more than publicly funded places, according to the UK parliament.

With the issues within care homes, the extensive press coverage and the ever-increasing demand for a public inquiry as to what has transpired in care home communities throughout the Covid-19 crisis, how many families will continue to keep loved ones in what is considered to be a ‘high-risk’ environment? How many families are going to move loved ones from residential to domiciliary care and remove their 1.4x funding from the residential sector? Breaking point for the sustainability of residential care sector is probably a 10% shift of self-funders leading to a collapse in provision of 400,000 beds in the private sector into a domiciliary service that is already close to collapse.

The quality of care that’s required, a reduction in the number of care providers, and the safety measures which now need to be applied, given that we have a live pandemic situation, add to this strain. Whichever way we look at this, there is either a looming disaster OR a great opportunity to fundamentally change OR a great opportunity to fundamentally change our approach to the delivery of care in the UK.

The technology-led opportunity for fundamental change in care delivery

Linking back to the work Agilisys did with NHSX and some of the technology solutions that we looked at from providers across the UK, it’s clear technology can play a big part in the future of social care.

Here’s a selection of the tangible ideas that can make a big difference.

Data is central to success

The Agilisys Helping Hands solution fixes one part of the problem. Roughly 2 million of the most at risk people across the UK who needed to shield based on age and co-morbidities, who needed some special care and attention if they were to survive the pandemic. What was painfully obvious was how the existing data distributed across health and local authorities had significant quality issues and a lack of cohesive integration between health and social care services.

Helping Hands digitised the front door to care allowing services to cleanse the information to a point where it supports the demand for care delivery to the at-risk cohort.

Helping Hands Explained

Helping Hands is a software solution initially designed to enable local government to contact and register the support needs of citizens shielding during Covid-19. It rapidly grew across seven Councils in Scotland and four in England to help authorities engage and maintain contact with approximately 300,000 citizens in just six-weeks from initial deployment.

Councils soon realised that the solution could also accommodate vulnerable and other citizens, where each individual authority had identified the possible need to provide rapid contact and intervention tracking (either inbound or outbound). Interventions such as pharmacy pick-up, food parcel delivery, emergency food requests, financial support needs and potential domestic abuse cases were all included in the questionnaire set by the councils.

Effectively, Helping Hands became a triage contact register, where after initial contact had been made, councils could quickly issue requests for a range of service interventions from appropriate internal specialists/SMEs and external providers, including from the third sector.

Management data could be monitored and reported in real-time, to aid in identifying resource needs promptly and effectively. The solution also accepted auto data-loading from NHS Shielding lists, which were provided on a regular basis.

Despite the cessation of NHS Shielding, several councils are seeking to continue with the solution and possibly expand its scope into a wider number of business and service lines.

Volunteers have a huge role to play – especially when connected by technology

The original request for 50,000 volunteers to come forward led to 750,000 people offering their time to complete well over half a million tasks in support of at-risk groups and those in need of care across the UK.

That was extremely useful, and while volunteer numbers will reduce as lockdown is relaxed and furlough schemes came to an end, it’s estimated that 500,000 people across the UK who are registered as volunteers, will be networked and connected via technology. That means tasks can be communicated to the right people with the right skills in a very short space of time and reduces the strain on traditional methods of social care delivery.

Video technology will remain at the fore

A lot of the technology we looked at with NHSX were remote care products, including the ability to have video calls with somebody to reduce the feelings of isolation.

Remote healthcare usage surged during Covid-19 – at the middle of July 2020, over 50% of medical consultations by GPs were performed via video, rather than face-to-face. This must be continued.

Every one of the 307 million GP appointments each year costs around £30 when include all costs such as property, heating, lighting, security and so on. If clinical appointments are carried out by a GP remotely via video, the number of appointments can increase – you can conduct 10 or so video consultations an hour as opposed to four or maybe five physical ones. The cost of delivering primary care in the UK drops substantially, which is something that we must do it we’re going to find a way through the budgetary challenge.

Steve Morgan explains how care at home will be displaced by technology.

Care at home will be increasingly displaced by technology

By deploying technology across people’s homes and linking it with the digitised front door, which is Helping Hands, we can displace a large proportion of attended care at home. The use of sensors like oximeters or door contact sensors that trigger an exception when dementia sufferers open doors at unexpected times, can reduce the number of home visits dramatically.

If we displace just 50% of attended care, a local authority with a cohort of 2,500 people in care would save roughly £10m a year. That’s a very conservative estimate. By using technology and our knowledge of the sector, there are some very large savings to be made, while improving the quality of service delivered.

‘Pseudo care plans’ will be adopted to ease the pressure on the creaking care system

Coming back to volunteers, within Helping Hands, we can develop a pseudo care plan that can tag and register not only volunteers, but family members, third sector organisations and charitable groups, who can be brought in to help when an exception is triggered. Each of those can determine what type of care are they going to provide, which could be doing some shopping, calling in and simply making sure people are eating, collecting repeat prescriptions or providing transport.

Within Helping Hand we can detail how, Ann Smith, for example, needs to go to the shops on Thursday afternoon; cook dinner for that evening and take her regular prescribed pharma. Her sister, Jean has registered to provide the transport and the shopping assistance as part of the pseudo virtual care plan. A neighbour has volunteered to cook meals for Ann and a local third sector organisation has arranged a rota service for medicinal care. We’re creating a support bubble around Ann and all other at-risk individuals – but it’s a bubble that could consist of 10,000 volunteers or organisations that bring different skills to the table, in addition to any formal care that would still be required.

Key to delivering the bubble is the digitised front door and capturing all members of the bubble, the service they will deliver and how that service is scheduled, all of which is available today within Helping Hands.

Central and local government have invested heavily in care, but the current situation demands additional targeted investment in finally integrating health and social care across the UK. Even the Prime Minister has stated in interviews, more than once, that care integration is a priority and hence we fully expect funding to be released from the treasury to fix the fundamental enabling technology and data challenges which make integration impossible and can bring residential and domiciliary care into the 21st century.

As an example, in 2019, 25% of residential care homes had no connection to the Internet. As we look at enhanced technology and data solutions, in parallel there are basic technology issues that need urgent attention.

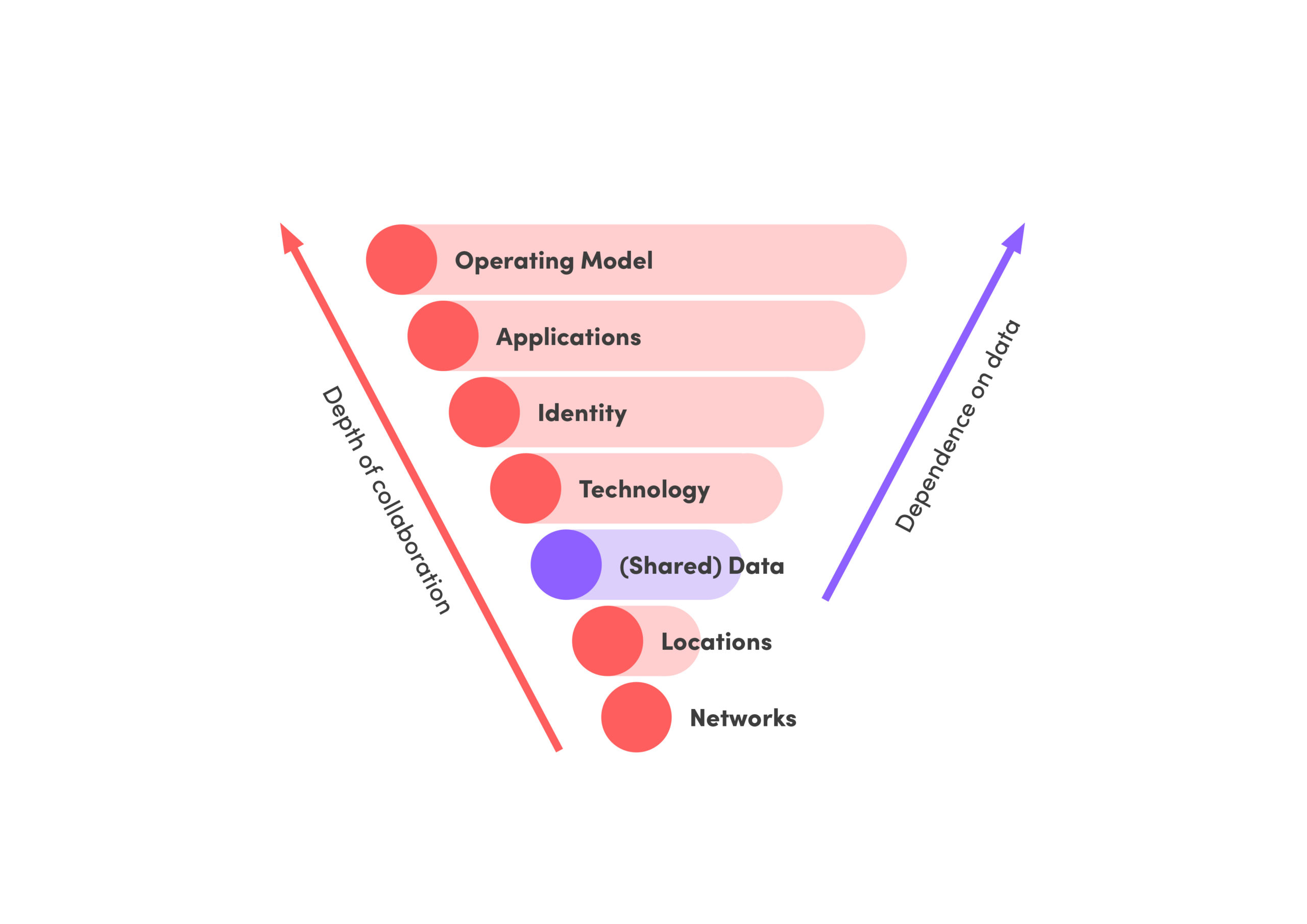

Integration of health and social care is more than co-locating people. If we are to see the benefits of the Care Act 2014 and make a difference in both the cost and quality of care across the UK, we need to integrate services across the full technology spectrum and also from a budgetary perspective, given that an investment with Adult Social Care within a local authority may give rise to a financial benefit elsewhere within the locality, e.g. within primary care. This, I believe was the intent of creating the locality-based integrated care organisations and integrated care systems (ICSs).

Contact centres will change forever

The well-documented changes to working habits will impact the delivery of social care. Local authority contact centres have typically been reactive, with the onus in the customer to share their challenges and instigate a response. In the post Covid-19 world, contact centre headcounts are reduced as home working takes over.

From a property perspective, we’re not going back to having consilidated groups of people in buildings. Instead, we’ll be looking at the technology offered by organisations such as 8X8 who are virtualising contact centres and delivering skills-based routing. That means you can virtually bring people, such as mental health care workers, who are home-based. And if you want to raise an exception that’s associated with one part of provisioning or social care, you’re able to do that automatically and immediately by using the relevant technologies.

Traditional local authority contact centres who operate an ‘inbound’ contact model must now change to a proactive ‘outbound’ contact odel, making video calls to citizens, verifying current situations and using the proactive support bubble and close integration with primary care (providing medical diagnosis via video consultation) in any exception event.

Early intervention using a proactive contact model will provide high levels of cost avoidance in preventing admission into acute care and better outcomes for the citizen.

Use of RPA and AI will accelerate

We are already seeing increased interest in chatbots to manage inbound demand – and we expect this to accelerate further and be supported by more complex Artificial Intelligence and Robotic Process Automation led solutions.

I think there’s a large amount of pent-up demand for council services – people have held off making requests but as the world returns to normal, they will do so. Therefore, the opportunities to signpost and manage that demand by automating it is an obvious example of how they can protect that service.

That’s vital because in ‘new’ care models as stated above, local authority resource will be required to manage more outbound contacts and hence reducing standards inbound demand will mitigate and potential resource challenge.

Case management systems will be replaced by solutions more suited to integrated care

The final piece that we have on the horizon is to do with case management systems for child and adult social care. Case management systems are complex, expensive to maintain and operate and tend not to support the integration and common access to information. The more we look at the information that is integrated into Helping Hands, the more we see how it will replace those care management systems and provide further incremental savings and benefits.

Conclusion: The idea of locality will finally be embraced

For me, what has been missing when looking at social care is for somebody to sit back and take holistic view, as to how existing technologies come together to deliver the outcomes that we need to see for vulnerable and isolated people.

Steve Morgan talks about how now is the time to embrace locality.

The work that we’ve been doing with NHSX addresses this and recognises that we have got to change the way we deliver social care, especially domiciliary care. Get the technology angle right and you can deliver change from a locality perspective, not just with local government but with the involvement of acute and community trusts, CGs, local authorities and the rest into that integrated care delivery model.

It’s clear to me, having been engaged with NHSX to review the technology solutions that can mitigate the impact of the Covid-19 on social care, that doing nothing is not an option. The pressure on the sector are severe – and have been seriously exacerbated by the pandemic – so now is the time to really bring technology to the fore

To achieve this, the three key actions we will be looking to drive across the care sector are:

Key action 1

As with any time of change, people need to be brave and make decisions through collaboration with thought leaders, public and private sector organisations. To support this, we will be initiating these collaboration sessions to drive the future care delivery model, including the data and technology integration with localities.

Key action 2

Create the business case for investment and fundamental change within a locality. We have used the £10m of domiciliary care costs mentioned earlier as a conservative estimate, so building a robust cost/benefit analysis quickly will support the decision-making group outlined above.

Key action 3

Extend our horizon scanning of the technology marketplace. The UK Techforce-19 initiative demonstrated how much technology innovation is being actively developed across the UK tech companies.

By identifying and fostering solutions, aligning tech solutions with known care issues and using our communication networks and relationships to position new and emerging tech in a manner that allows it to be exploited quickly, we are confident that the UK care sector will be brought into the 21st century.

Most importantly, by doing this the quality of life for the UK’s most disadvantaged will be vastly improved – which is surely all the motivation we need to drive lasting change.