Addressing the epidemic of loneliness in the wake of COVID-19

We are living through a period of crisis. That statement seems blindingly obvious, given everything that has been going on around the world in the last year or more, but I’m not talking about COVID-19, but about loneliness. Prior to the COVID crisis, the UK government had identified loneliness as a significant public health issue, […]

We are living through a period of crisis. That statement seems blindingly obvious, given everything that has been going on around the world in the last year or more, but I’m not talking about COVID-19, but about loneliness.

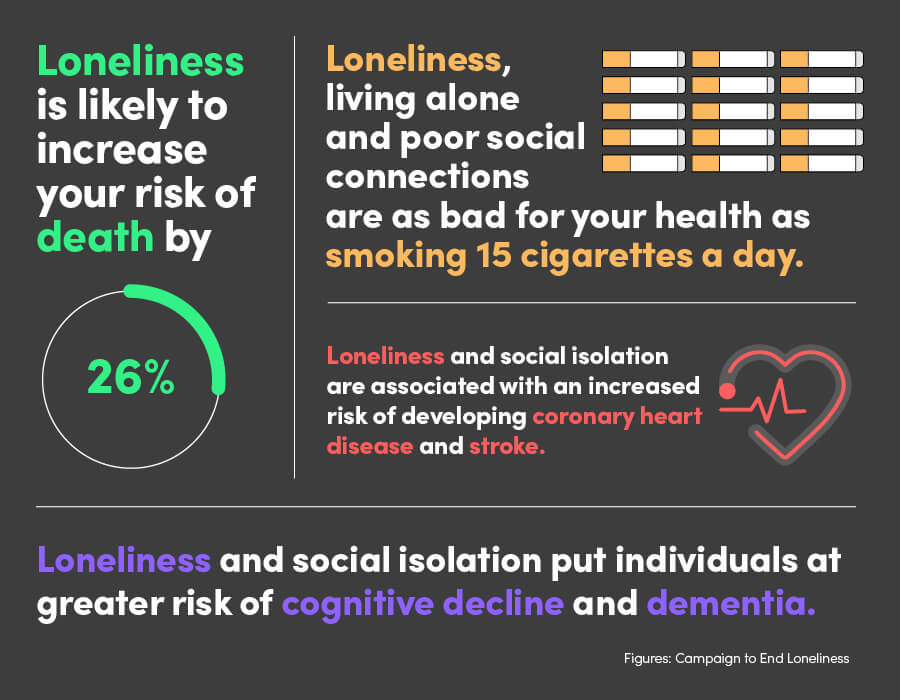

Prior to the COVID crisis, the UK government had identified loneliness as a significant public health issue, and it has been described as an epidemic. Just like coronavirus it’s pervasive, penetrating all areas of our society. It’s infections. It’s likely to increase your risk of death by 26%. And it’s not just a disease of the elderly despite the media perception. It’s a problem that touches everyone in society, directly or indirectly. Yet, there’s no one-size-fits-all vaccine to cure the social problems of loneliness and isolation; there’s no magic solution on the horizon, which means we’re facing a ticking time bomb that requires rapid action to defuse.

In this report, we discuss the major issues fuelling this new epidemic and provide an overview of what measures need to be taken across the public sector if we are to address the issue. We also detail how technology can lead the responses to the crisis and enable fundamental change in how society prevents loneliness and isolation from spiralling out of control.

The pressures of a pandemic

The epidemic of loneliness was already worrying governments, scientists and health professionals long before coronavirus arrived. UK mental health services are straining to allocate resources to support the growing number of people with mental health problems; and given the upsurge of service demand because of the psychological sequela of COVID-19, those pressures will be magnified.

In his 2020 book, Epidemics and Society, Snowden claims that pandemics hold up a mirror to society that reveals both the dark and heroic components of our world. The COVID-19 pandemic means we exist in a space filled with tension – we’re desperate to connect but prevented from doing so for our own good, and the good of others. It’s in our human make up to want to hold those closest to us, and comfort those who need it most. Furthermore, masks make it difficult to read faces, to see unhappiness or worry or even sheer happiness at connecting in some way, while the general fear of contagion further disincentivises mingling and exacerbates the problem.

This is a worry for society as a whole – and especially for organisations across the public sector. Numerous studies have found loneliness is associated with a range of health problems – from addictions and depression to heart disease – and shorter life expectancy.

It’s worth pointing out that age is not a valid predictor of loneliness. According to a Mental Health Foundation survey of UK adults which took place nine months into COVID-19 restrictions (late November 2020) one in four (24%) adults in the UK said they had feelings of loneliness in the “previous two weeks”.

Loneliness levels were higher in young people, people who are unemployed, full time students and single parents in each wave of the survey tracking the mental health of the nation since March.

According to the Campaign to End Loneliness:

1. The number of over-50s experiencing loneliness is set to reach two million by 2025/6. This compares to around 1.4 million in 2016/7 – a 49% increase in 10 years.

2. A survey by Action for Children found that 43% of 17 – to 25-year olds who used their service had experienced problems with loneliness, and in this same group, less than half said they felt loved.

3. Research by Sense has shown that up to 50% of disabled people will be lonely on any given day.

Government enforced lockdowns taking place worldwide could potentially open the Pandora’s box of loneliness; affecting new groups of people, people who have not experienced loneliness before.

The need for action

Steve Morgan discusses what impact the epidemic of loneliness will have on the public sector.

The impact on the public sector

If we can take the right actions and utilise the skills of people in the right way, the hope is that we can get people who have been removed the loneliness epidemic to go on to help other people in similar situations. That’s the success story we should look for.

The problem of responsibility

As we’ve already discussed, loneliness and isolation were a problem long before COVID-19 arrived – and some of the problem is about responsibility – and signposting to the relevant available help:

1. The Department of Health and Social Care will say: “Those suffering from loneliness have not presented with any issues. They may have some challenges in terms of lack of integration of the community or community support. And if it’s a community support issue that belongs with the local authority”.

2. Local authorities would, in turn, say: “Well, not really, because they’re not in receipt of a care plan. Therefore, if they don’t meet the requirements of social care, which they don’t, it’s a family issue. Or if they don’t have any family, it’s over to the community groups”.

3. The community groups will probably say: “Well, we’re woefully underfunded, we have a lack of resource, therefore we will look at this, but we may not get round to it in a timely manner”.

One good reason to act

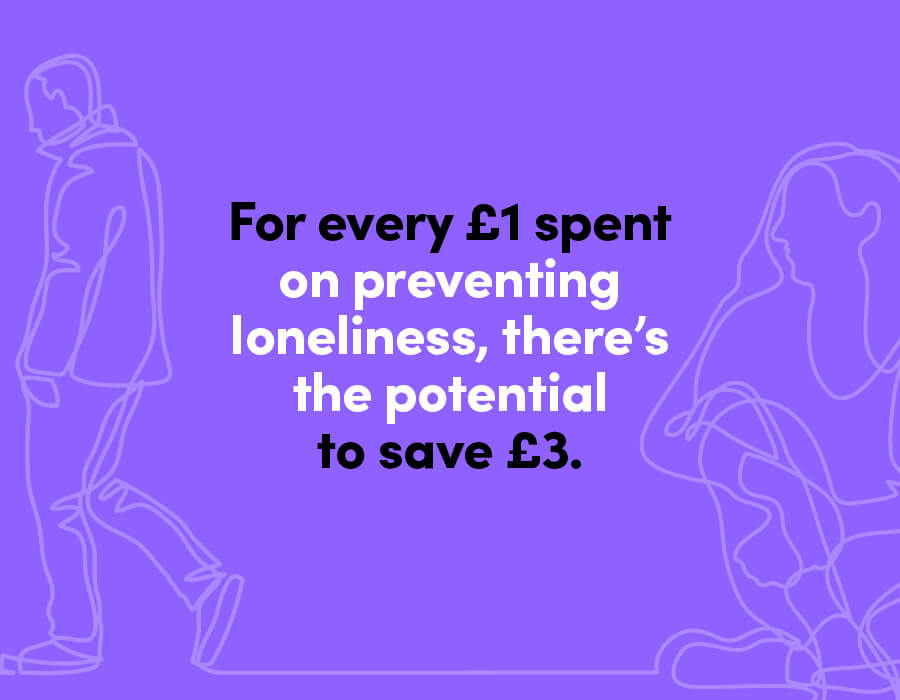

Numerous studies have tried to put a figure on the cost of the UK’s epidemic of loneliness. For me, one stat stands out: researchers from the LSE estimate that for every £1 spent on preventing loneliness, there’s the potential to save £3.

The crux of the issue here is that we need to think about the situation differently. We know loneliness is a significant contributor to mental health problems. If we are able to intervene, and to stop people presenting with mental health issues caused by loneliness and isolation, there’s a cost saving, a return on investment.

If there is an intervention from a mental health trust for 12 months, costs start at approximately £150,000 per individual. If you addressed the loneliness – the cause of the intervention in the first place – through a network of individuals, which includes the voluntary sector, some intervention from social care, and some technology, I would be very surprised if the cost would not reduce to circa £30,000 a year.

You can take this thinking a step further. Research by Florida State University shows that loneliness can increase the risk of dementia by 40%. Add in the body of evidence that demonstrates if somebody with the beginnings of dementia is taken into a mental health trust, they go downhill rapidly, especially if they are elderly and you can see the need to nip the cause in the bud. Acute intervention is often the worst possible avenue for people with these types of issues.

Tackling the epidemic of loneliness through tech

The challenges of dealing with a growing epidemic are well publicised – and nothing new. However, as we’ve already discussed, those problems have been exacerbated by COVID-19. There are, however, several technology-led steps that can be taken to bring the epidemic of loneliness under control, which build on Government’s Connected Society – A strategy for tackling loneliness paper.

It talks about maximising the power of digital tools to connect people, particularly concentrating on digital inclusion for older and disabled adults, and addressing loneliness in the forthcoming white paper on internet safety. Overall, it champions technology as a real force for social good.

Here, Steve Morgan explores why we must use technology to tackle the epidemic of loneliness.

Create a better picture of the need

Estimates vary (often wildly) regarding the number of people across the UK who are often or always lonely. And this disparity is concerning. If we can’t measure and record loneliness correctly, what hope do we have of dealing with the issue? The way loneliness is measured in England is pitiful. One 100% subjective question in an annual survey is unlikely to give any real data to work with.

Therefore, finding a better way to capture the data is surely the only starting point of any meaningful action.

Only when we get the data right can we join up thinking around health and social care and start to deliver the most suitable interventions. We know the loneliest cohorts are at risk of cognitive impairment and are more likely to move further into the healthcare system, but how do we get the data that we need flowing across organisational borders? Third sector organisations such as MIND hold rich data, but we just don’t use it the way we should. It’s not joined up.

The University of California recommends three questions, with three clear answer choices for each of the questions (hardly or never, some of the time, often) to provide a more objective answer than the one that we use in England.

1.How often do you feel that you like companionship?

2.How often do you feel left out?

3.How often do you feel isolated from others?

This method provides some form of measurement. As well as enabling organisations to identify bands of the most isolated or lonely individuals, it also enables the effectiveness of any intervention to be measured. Regularity and patterns are also something we should start to think about. If we had a digitised version of the question people could answer every day, then we would spot patterns/early deterioration early, which of course enables early intervention.

Digitise the front door to care

At the beginning of the first COVID-19 lockdown, Agilisys developed Helping Hands, a data-focused solution that at-risk people and their needs. By using a solution such as Helping Hands as the vehicle to identify the most at-risk cohort, you create the ability for a care plan to be delivered, bringing those people more effectively into society.

A data solution can also be useful in bringing together bandings of loneliness. And then how do you implement that and get that out in a manner where you can quickly identify those people most at risk that we need to do something about.

Engaging with people on subjects that matter to people. A study found that music is something that’s very helpful for those people who are feeling isolated. If you can identify the type of music that an individual likes to listen to and give them a vehicle where they can actually listen to it, even if they’re singing along alone, it brightens their day.

Helping Hands Explained

Helping Hands is a software solution initially designed to enable local government to contact and register the support needs of citizens shielding during Covid-19. It rapidly grew across seven Councils in Scotland and four in England to help authorities engage and maintain contact with approximately 300,000 citizens in just six-weeks from initial deployment.

Councils soon realised that the solution could also accommodate vulnerable and other citizens, where each individual authority had identified the possible need to provide rapid contact and intervention tracking (either inbound or outbound). Interventions such as pharmacy pick-up, food parcel delivery, emergency food requests, financial support needs and potential domestic abuse cases were all included in the questionnaire set by the councils.

Effectively, Helping Hands became a triage contact register, where after initial contact had been made, councils could quickly issue requests for a range of service interventions from appropriate internal specialists/SMEs and external providers, including from the third sector.

Management data could be monitored and reported in real-time, to aid in identifying resource needs promptly and effectively. The solution also accepted auto data-loading from NHS Shielding lists, which were provided on a regular basis.

Despite the cessation of NHS Shielding, several councils are seeking to continue with the solution and possibly expand its scope into a wider number of business and service lines.

Technology led solutions

Bring people together at scale

Much in the same way a virus is a threat to clinical health, loneliness is a threat to mental health. And just as we would shape care according to the clinical health need, we must tailor care to the mental health need. The big difference is that one of the simplest answers to loneliness and social isolation is connection with other individuals – meaning there’s the opportunity to address the needs of multiple individuals at one time. Social prescribing has a role to play too.

As was discussed in my previous paper around health and social care postCVOID-19, over 750,000 people offered their time to complete more than half a million tasks in support of at-risk groups and those in need of care across the UK during the pandemic. If we can network and connect available volunteers via technology, tasks can be communicated to the right people with the right skills in a very short space of time.

Add in connections into community groups and third sector organisations and we have a large network of people who can be mobilised to deploy an anti-loneliness care plan to isolated people at risk – or simply take a neighbour to their local library, Pandemic permitting, of course.

The contact centre model must be reimagined

Traditional local authority and/or mental health provider contact centres – so used to running on an ‘inbound’ contact model, must now change to a proactive ‘outbound’ contact model, making video calls to citizens, verifying current situations, and using the proactive support bubble and close integration with primary care and community services in any exception event.

This can be assisted through the use of contact centre technology from the likes of 8×8, which is virtualising contact centres and delivering skills-based routing. That means you can virtually bring in people, such as mental health care workers, who are home-based. And if you want to raise an exception that’s associated with one part of provisioning or social care, you’re able to do that automatically and immediately by using the relevant technologies.

Connect through effective technology

Of course, it’s incredibly important during this pandemic for people in the highest risk groups to remain cautious about meeting others. Loneliness can still be tackled, but from a safe distance, which is where technology clearly has a role to play.

One of my greatest frustrations is that the over 75’s are the fastest growing population of those people who access the internet. And everybody uses the fact that ‘well, they’re old and therefore, you know, they’ve got no digital skills’ almost as an excuse to do nothing. There are going to be people who will need to be oriented in terms of how to use technology, but many older people who are lonely are digitally savvy and others can learn new skills.

I appreciate there’s a bigger challenge with individuals who have some form of cognitive impairment, which means that they may have difficulty initially. But that’s a problem for us to solve. We need to make the consumption of digital as easy as turning on a tap; we’ve already seen the use of voice commands via Amazon’s Alexa make strides, while smart devices have been rolled out in large quantities to reduce social isolation. This is just the tip of the iceberg as it’s eminently possibly to make technology easy enough to consume by those often denigrated simply because they have a cognitive impairment. This does not need to automatically equal digital exclusion.

Getting it right: an example

The good news is that there are many organisations doing some great work, including Barking and Dagenham’s innovative Citizens Alliance Network (BDCAN).

Cllr Maureen Worby, cabinet member of social care and health integration at Barking & Dagenham LBC, wrote in The MJ, “BDCAN offers coordinated practical help and support for tens of thousands of vulnerable residents. It reaches significantly more people than those on the NHS Shielding list. We know more residents who could benefit from it.

“The key to BDCAN is that it is not a one-person show. Instead, it is co-led by the council and a collection of around 80 community and faith organisations that make up the civic society of our borough. It makes regular contact with almost 1,000 residents over the phone and carries out over 500 home visits. Going forward, it has the potential to offer a lifeline for those suffering from isolation who are without informal means of support.

People want a hand up, not a handout. This is what BDCAN offers by strengthening engagement and offering to empower them.

“BDCAN stepped in when food parcels and prescriptions needed to be delivered during the pandemic. The network is now working together to keep in touch with those for whom loneliness is the wolf at the door.”

Conclusion: Care needs to come before intervention

If you go back to the 1950s and 1960s, events such as tea dances got people out of their homes and into a place where, to be honest, they had to engage with other people, because they couldn’t avoid them. They are the sorts of social gatherings that have disappeared.

Fast forward to today and technology advances that make life more seamless – and apparently connected – actually displace established communities and create circumstances that make it harder to form social bonds. Contactless payment, self-serve checkouts and online shopping remove us from micro-interactions, such as small talk with a cashier.

Faced with a damaging epidemic, we need to find ways to replace interactions and to bring people back together, even if that means doing it virtually.

Imagine the story where there are some isolated, individuals within communities, who are feeling very isolated, who don’t have real contact with people. If we’re able to identify those people as being at risk, the quickest mass intervention can happen using technology, community groups, third sector people, integrating maybe with neighbourly contact. Technology can become a greater part of the solutions, and less of the problem. If we can take the right actions and utilise the skills of people in the right way, the hope is that we can get people who have been removed from the loneliness epidemic to go on to help other people in similar situations. That’s the success story we should look for.

Above all else, we need to start caring about our population before they need intervention. We need to take a preventative approach. There’s no single organisation that can fix any of these issues. People need to work together to solve the challenges… and we need to do it quickly.

Steve Morgan discusses how we can create an expanding circle of support.

Three key actions the public sector needs to take

1. The current method of measuring loneliness is wholly subjective and does not provide an accurate view of the issue nor provide data that can be used to form solutions. Adopting the University of California approach will improve the quality of the captured data.

2. The success of solutions such as BDCAN are wholly dependent on the community working together to tackle the issues residents are facing. Developing a community trust model that is focussed on helping those in need is a must if we are to change the lives of the vulnerable and isolated within our communities.

3. We have worked tirelessly to build solutions that help in identifying and engaging the most at-risk within the community (Helping Hands), this service must be extended to track those that are feeling the effects of isolation and loneliness, build the person-centric support bubble and define virtual care plans that can have a positive impact.